Argentina’s inflation problem: The price of cooking the books

marzo 2, 2012

Argentina’s inflation problem: The price of cooking the books

History has left Argentines with more than their share of economic trauma. Having twice suffered destructive bouts of hyperinflation in the late 1980s, they are sensitive to rising prices. When they spot inflation their instinct is to dump the peso and buy dollars. But after the economy collapsed in 2001-02, horror at mass unemployment temporarily eclipsed the public’s fear of inflation. That has been the successful political calculation of the president, Cristina Fernández, and her late husband and predecessor, Néstor Kirchner. For years they stoked an overheating economy with expansionary policies. Faced with the resulting rise in inflation, their officials resorted to price controls—and to an extraordinarily elaborate deception to conceal the rise.

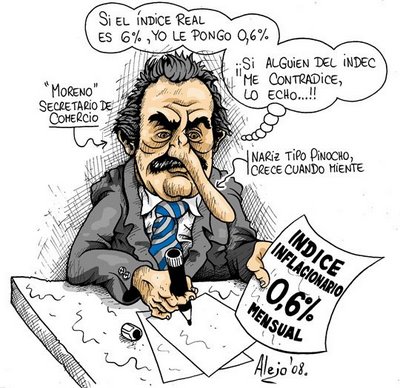

Since 2007, when Guillermo Moreno, the secretary of internal trade, was sent into the statistics institute, INDEC, to tell its staff that their figures had better not show inflation shooting up, prices and the official record have parted ways. Private-sector economists and statistical offices of provincial governments show inflation two to three times higher than INDEC’s number (which only covers greater Buenos Aires). Unions, including those from the public sector, use these independent estimates when negotiating pay rises. Surveys by Torcuato di Tella University show inflation expectations running at 25-30%.

PriceStats, a specialist provider of inflation rates which produces figures for 19 countries that are published by State Street, a financial services firm, puts the annual rate at 24.4% and cumulative inflation since the beginning of 2007 at 137%. INDEC says that the current rate is only 9.7%, and that prices have gone up a mere 44% over that period.

INDEC seems to arrive at its figures by a pick-and-mix process of tweaking, sophistry and sheer invention. Graciela Bevacqua, the professional statistician responsible for the consumer-price index (CPI) until Mr Moreno forced her out, says that he tried to get her to omit decimal points, not round them. That sounds minor—until you calculate that a 1% monthly inflation rate works out at an annual 12.7%, whereas 1.9% monthly compounds to 25.3%.

Threatening letters sent by the government to independent economists also shed light on INDEC’s methods. One was told that since the cost of domestic service was “a wage, not a price”, he should not have included it in his CPI calculations. “They have put a lot of effort and lawyers into such arguments,” he says.

Ana María Edwin, INDEC’s current boss, is unrepentant. In Ms Bevacqua’s day, INDEC artificially boosted the inflation rate, perhaps to benefit holders of inflation-linked bonds, she claims. She hints at underhand, possibly criminal, dealings between former INDEC staff, independent Argentine economists and international financiers. The evidence? That agreements between Mr Moreno and retailers to cap prices of basic products were not reflected in INDEC’s calculations before 2007. That suggests INDEC is now using some government-mandated prices rather than those that consumers actually pay.

When a product’s price spikes, INDEC takes it out of the CPI basket. “Poor people don’t just keep buying things if their price goes up a lot,” Ms Edwin explains. “They think: I will leave those tomatoes for the rich.” A proper CPI calculation does indeed involve rules for dealing with changes in buying patterns. But the potential for abuse is clear.

Some Argentine government bodies seem well aware of the true inflation rate. Foreign investors report presentations by the Central Bank mentioning a real (ie, inflation-adjusted) exchange rate that implies annual inflation of around 20%. Economists who have picked through the somewhat suspect figures for economic growth say they can discern a similar rate in the “deflator” used to correct some prices. Perhaps most intriguingly, INDEC’s and PriceStats’ inflation rates accelerate and decelerate in tandem.

The government has gone to extraordinary lengths, involving fines and threats of prosecution, to try to stop independent economists from publishing accurate inflation numbers. The American Statistical Association has protested at the political persecution faced by its Argentine colleagues, and is urging the United Nations to act, on the ground that the harassment is a violation of the right to freedom of expression.

At the government’s request, last year the IMF sent experts to help it plan a new national CPI. Ms Edwin says that the new index will not be ready until early 2014.

The longer this deception goes on, the trickier it is for the government to end. Faced with deteriorating fiscal accounts, Ms Fernández has begun to trim subsidies amounting to 5% of GDP. Their removal will push prices up further—as would a weakening of the peso. So Mr Moreno’s latest wheeze involves responding to a vanishing current-account surplus with strict import controls, which will undermine growth. Argentina has created a statistical labyrinth that might have been dreamed up by Jorge Luis Borges, the country’s greatest writer. This story is unlikely to have a happy ending.

Source: The Economist (UK), marzo 2012.